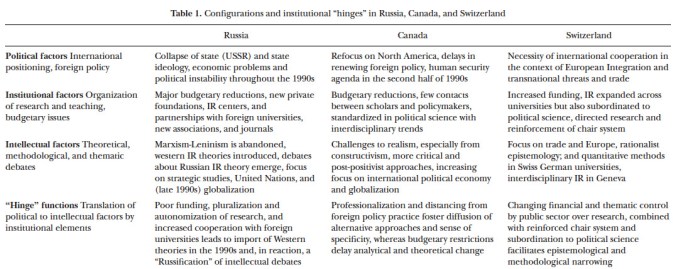

It is generally accepted today that major international events – such as in 1914, 1945, 1989 or 2001 – contribute to guiding IR scholarship’s interests. But it remains poorly explored how, beyond substantive focus, transformative political events affect the academic field’s own working and organization. Whereas we know that global key moments (such as the end of the Cold War) were or are experienced differently by different societies, at the policy level, in terms of identity-construction and historiography, it remains to explore how such changes influence scholarly work in different higher education systems. Our article in International Studies Perspectives focuses on this link. It centers on the role of institutional factors in the conditioning of IR scholarship, which it sees as important yet under-explored intervening elements in the interrelation between political events and academic practice. The article defines the utility of such focus and illustrates it with casework centering on the end of the Cold War, and three central parties to the Cold War conflict – Russia as representative of the Eastern Bloc, Canada of the Western Alliance, and Switzerland as a Neutral polity. In doing so, the article showcases how institutional factors such as funding schemes, the marketization of education or creation of new IR departments operate as effective ‘hinges’, exerting significant influence over the ways scholars develop ideas about international relations.

It is generally accepted today that major international events – such as in 1914, 1945, 1989 or 2001 – contribute to guiding IR scholarship’s interests. But it remains poorly explored how, beyond substantive focus, transformative political events affect the academic field’s own working and organization. Whereas we know that global key moments (such as the end of the Cold War) were or are experienced differently by different societies, at the policy level, in terms of identity-construction and historiography, it remains to explore how such changes influence scholarly work in different higher education systems. Our article in International Studies Perspectives focuses on this link. It centers on the role of institutional factors in the conditioning of IR scholarship, which it sees as important yet under-explored intervening elements in the interrelation between political events and academic practice. The article defines the utility of such focus and illustrates it with casework centering on the end of the Cold War, and three central parties to the Cold War conflict – Russia as representative of the Eastern Bloc, Canada of the Western Alliance, and Switzerland as a Neutral polity. In doing so, the article showcases how institutional factors such as funding schemes, the marketization of education or creation of new IR departments operate as effective ‘hinges’, exerting significant influence over the ways scholars develop ideas about international relations.

Grenier, Félix; Hagmann, Jonas; Lebedeva, Marina; Nikitina, Yulia; Biersteker, Thomas; Koldunova, Ekatarina (2020). The institutional ‘hinge’: How the end of the Cold War conditioned Canadian, Russian and Swiss IR scholarship. International Studies Perspectives 21(2): 198-217. PDF

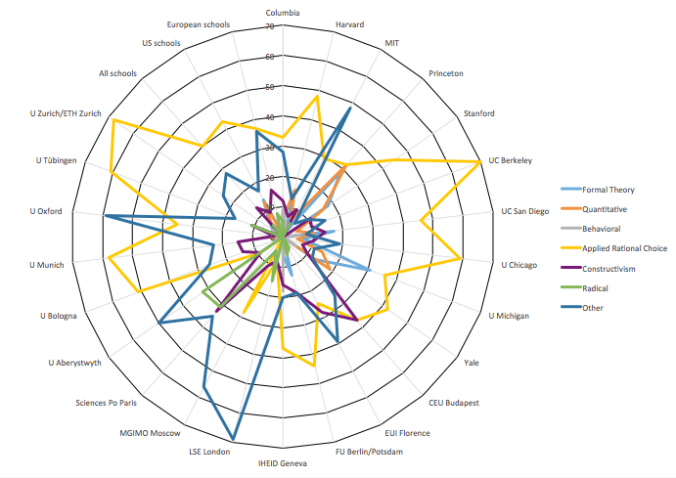

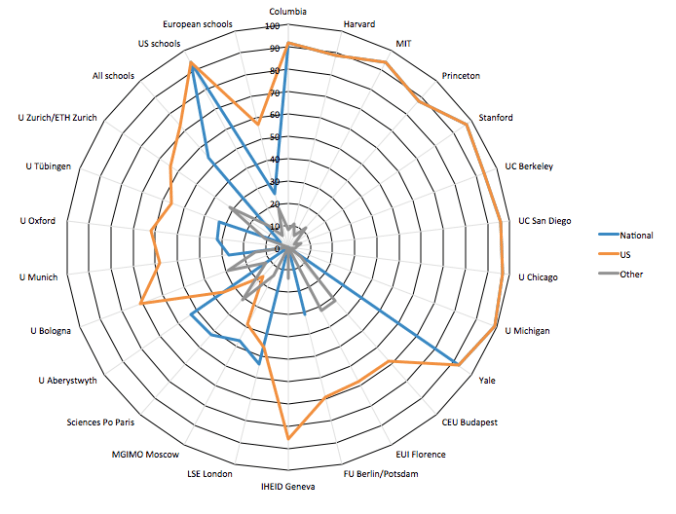

Publication metrics are preferred measures of the academic discipline called International Relations (IR). Yet, article writing is not all what scholars do, and indicators focusing on other scholarly activities – such as most notably, teaching – draw other pictures of intellectual hierarchy in the field. In the newly minted SAGE Handbook of the History, Philosophy and Sociology of International Relations, Tom Biersteker and I propose to also approach IR as a pedagogical field. Drawing on an extended empirical data-collection effort, we look at and dis-aggregate the core IR courses of 23 Western universities in terms of paradigmatic penchants and intellectual origins. In doing so, our ambition is to problematise popular and powerful cartographies of international scholarship, and to define academic work in more comprehensive – and dare one say, balanced – ways.

Publication metrics are preferred measures of the academic discipline called International Relations (IR). Yet, article writing is not all what scholars do, and indicators focusing on other scholarly activities – such as most notably, teaching – draw other pictures of intellectual hierarchy in the field. In the newly minted SAGE Handbook of the History, Philosophy and Sociology of International Relations, Tom Biersteker and I propose to also approach IR as a pedagogical field. Drawing on an extended empirical data-collection effort, we look at and dis-aggregate the core IR courses of 23 Western universities in terms of paradigmatic penchants and intellectual origins. In doing so, our ambition is to problematise popular and powerful cartographies of international scholarship, and to define academic work in more comprehensive – and dare one say, balanced – ways.