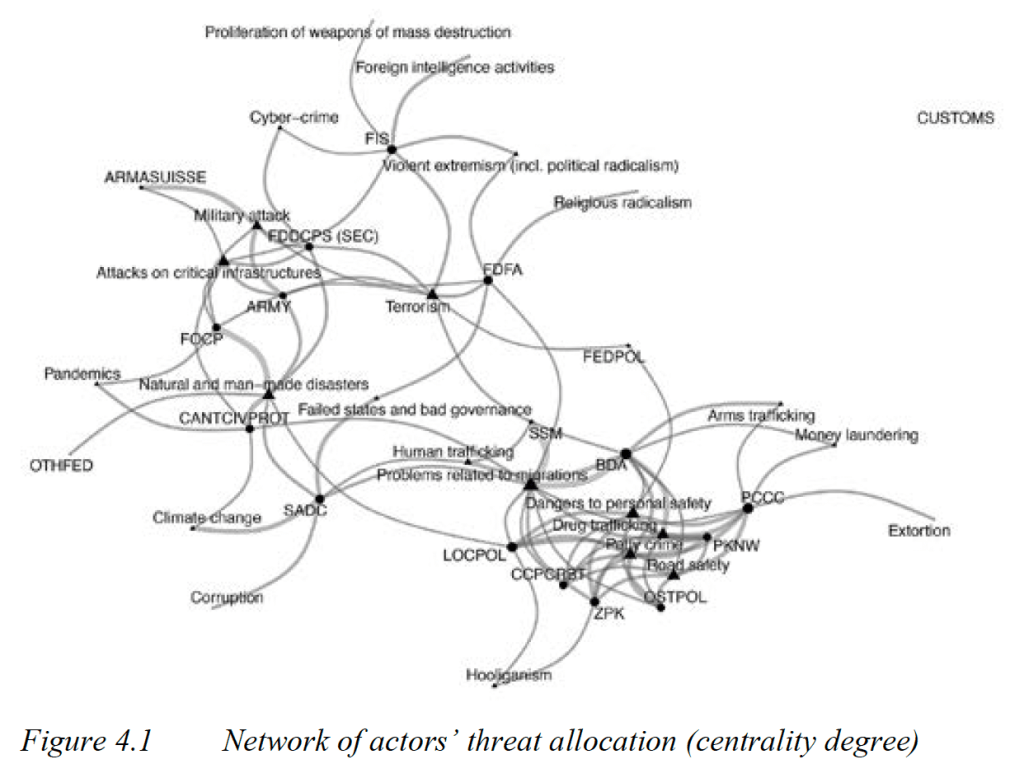

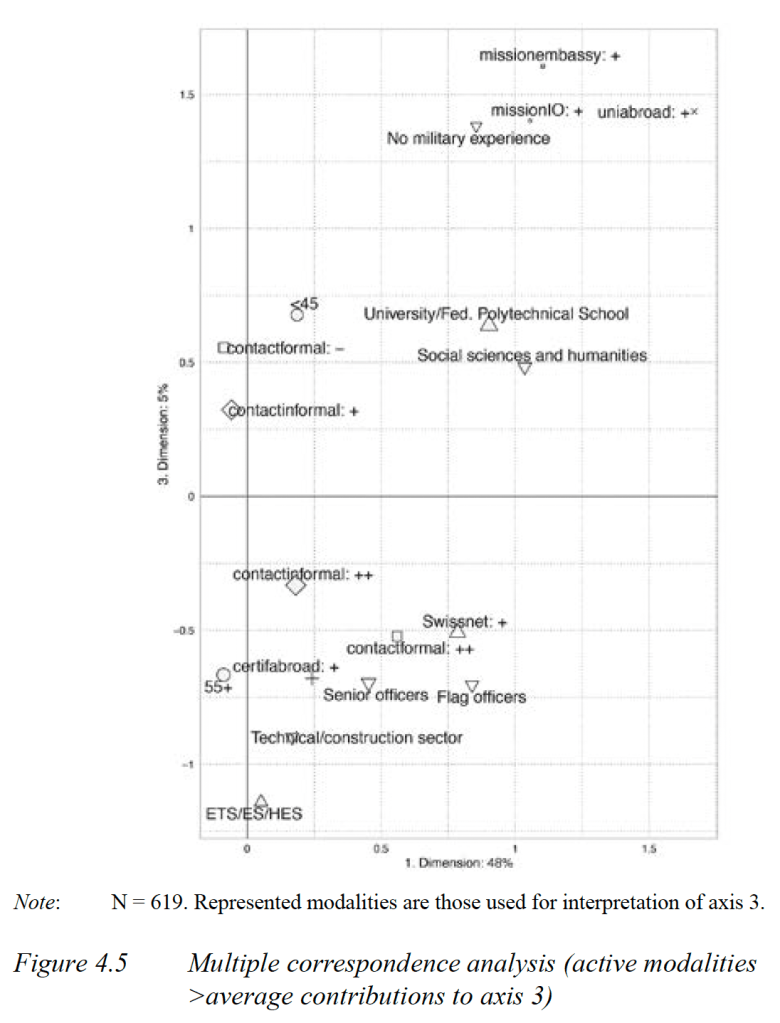

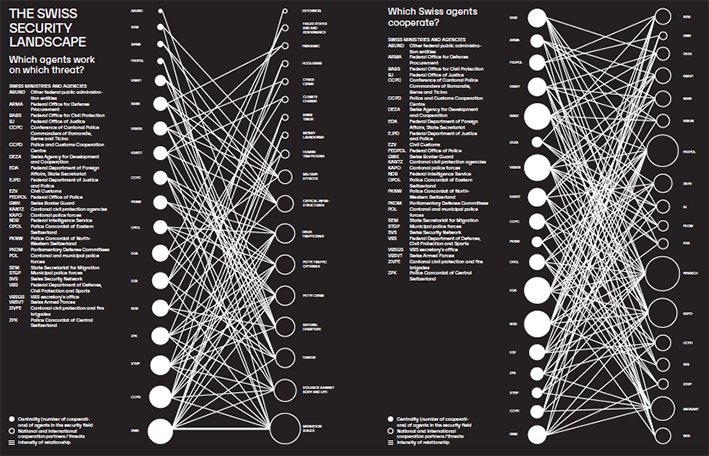

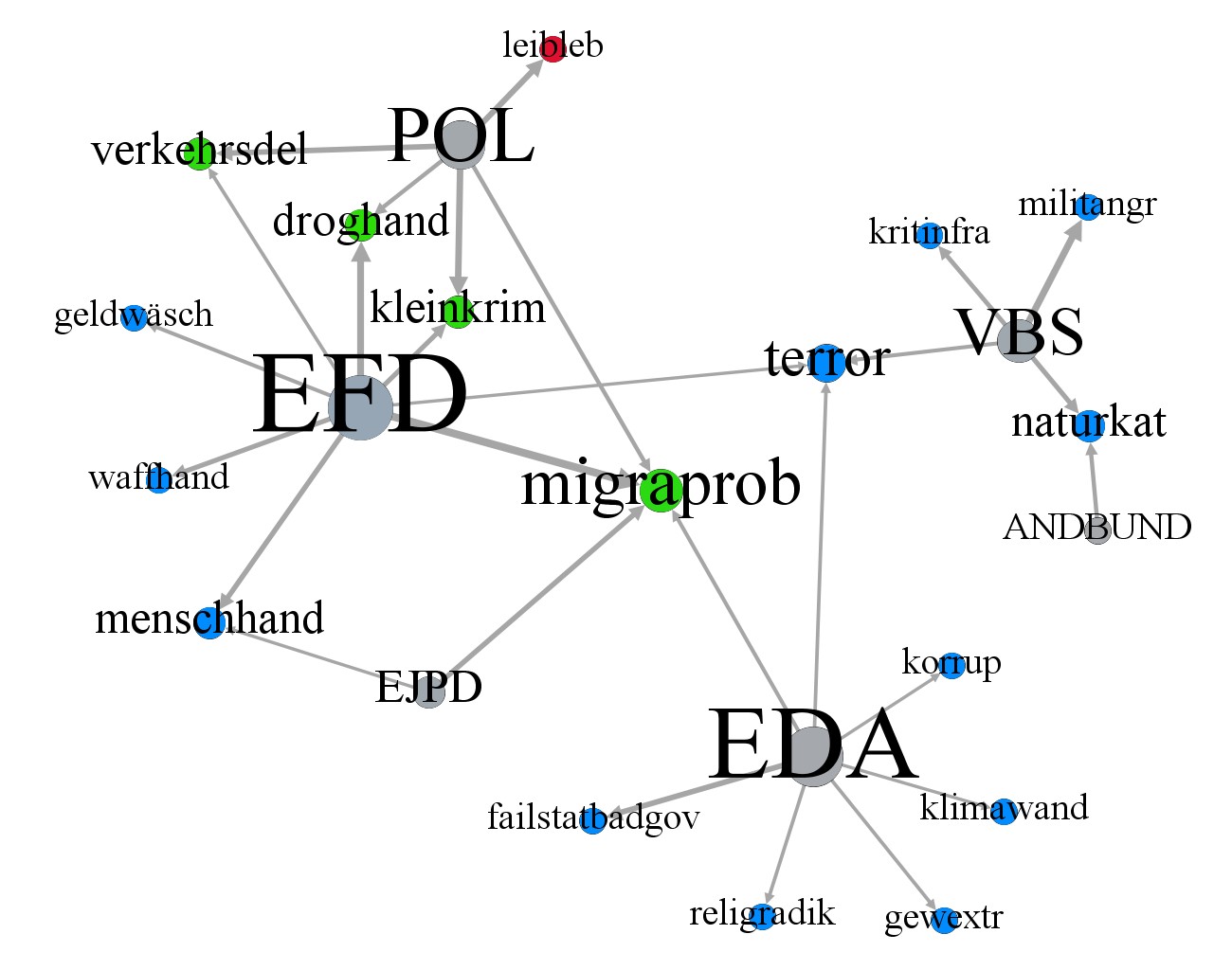

National security policy defies easy analysis. State action in the security domain is extraordinarily diverse and wide-ranging, stretching from defense and diplomacy to civil protection, public order and social security. As a result, conventional differentiations – such as between internal and external security, police and military, or public and private security production – became outdated and do not provide sufficient analytical to understand how the national security is configured and evolving. Bourdieu’s field theory is one useful way to better capture the complexity of the national security domain. In its view, the numerous specialists active in the domain form a larger professional space, whose inner workings are co-determined by positions, knowledges, individual skills and professional practices that may themselves be competing with one another. The chapter sets out this understanding and offers a deep empirical account of the Swiss national security field’s (re-)configuration in the 2010s. It shows what actors worked on what kind of security challenge(s) and in collaboration with whom, and it charts the forms of ‘capital’ (education, professional experiences, military ranks etc.) on which these practices were drawing.

Who work on what threats? The production of national security in Switzerland in the 2010s

On what forms of ‘capital’ are the practices based? Switzerland in the 2010s

Davidshofer, Stephan; Tawfik, Amal; Hagmann, Jonas (2024). Security as a field of force: the case of Switzerland in the mid-2010s. In: Dubois, Vincent (ed.). Bringing Bourdieu’s Theory of Fields to Critical Policy Analysis, pp. 74-89. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. PDF

What does it take to safeguard a country like Switzerland? And is the national security system, which exudes certainty to those controlled by its agents, indeed as fortified as it appears? This essay chapter in Salvatore Vitale’s photographic visual study of 21st century statehood discusses the history and political sociology of the Swiss national security field. It lends a special eye to the the authorities capable of defining what security is or ought to be about, and asks whether the field has become more accessible and participatory in recent years.

What does it take to safeguard a country like Switzerland? And is the national security system, which exudes certainty to those controlled by its agents, indeed as fortified as it appears? This essay chapter in Salvatore Vitale’s photographic visual study of 21st century statehood discusses the history and political sociology of the Swiss national security field. It lends a special eye to the the authorities capable of defining what security is or ought to be about, and asks whether the field has become more accessible and participatory in recent years.

It is widely known that national security fields changed considerably in the last decades. Different from the late Cold War years, when they focused on military threats, were closely orchestrated by Defence Ministries and contained few international contacts, national security ‘systems’ today handle wide sets of dangers, draw on complex casts of actors across levels of government, and often maintain working relations with multiple foreign partners. This comprehensive reconfiguration of national security fields is a central theme to security scholars and policymakers alike – but also difficult to pin down for methodological reasons. Written documentation on security agencies does not give precise indication of actual everyday inter-agency work practices, and assessments of nationwide security work across functions and levels of government are challenging by sheer questions of size. Adopting a practice-oriented approach to security research, this article draws on an unparalleled nationwide data collection effort to differentiate and map-out the Swiss security field’s programmatic and institutional evolution.

It is widely known that national security fields changed considerably in the last decades. Different from the late Cold War years, when they focused on military threats, were closely orchestrated by Defence Ministries and contained few international contacts, national security ‘systems’ today handle wide sets of dangers, draw on complex casts of actors across levels of government, and often maintain working relations with multiple foreign partners. This comprehensive reconfiguration of national security fields is a central theme to security scholars and policymakers alike – but also difficult to pin down for methodological reasons. Written documentation on security agencies does not give precise indication of actual everyday inter-agency work practices, and assessments of nationwide security work across functions and levels of government are challenging by sheer questions of size. Adopting a practice-oriented approach to security research, this article draws on an unparalleled nationwide data collection effort to differentiate and map-out the Swiss security field’s programmatic and institutional evolution.

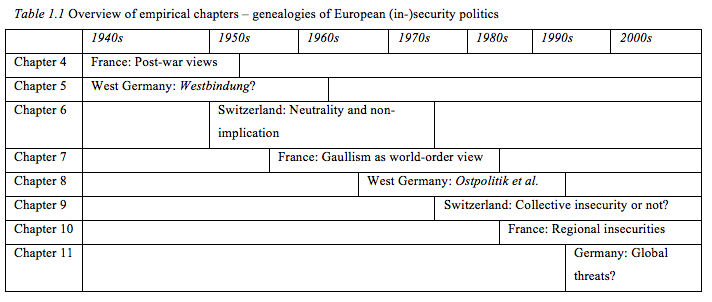

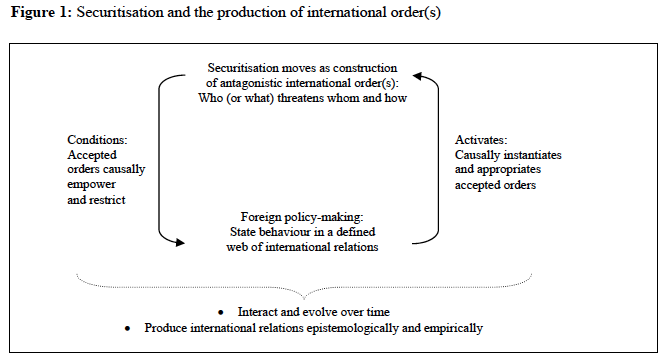

How do notions of collective international insecurity come about, and what are their effects on foreign policy-making? The Copenhagen School’s securitization theory offers a powerful take on the political construction of threats. In its original variant, however, the theory focuses strongly on the deontic (norm-breaking) powers of ‘security talk’ – and not on the threat sceneries that the latter substantively describes. This article addresses this latter link by reworking securitization into a positional/relational argument. Seen its way, the framing of something as threatening comes with larger – often implicit – claims about threatening and threatened actors in world politics. The empirical cases on post-war France and West Germany show how securitization equals an epistemological systematization of international affairs, for the political construction of collective international danger becomes an ordering process that conditions foreign policy strategizing.

How do notions of collective international insecurity come about, and what are their effects on foreign policy-making? The Copenhagen School’s securitization theory offers a powerful take on the political construction of threats. In its original variant, however, the theory focuses strongly on the deontic (norm-breaking) powers of ‘security talk’ – and not on the threat sceneries that the latter substantively describes. This article addresses this latter link by reworking securitization into a positional/relational argument. Seen its way, the framing of something as threatening comes with larger – often implicit – claims about threatening and threatened actors in world politics. The empirical cases on post-war France and West Germany show how securitization equals an epistemological systematization of international affairs, for the political construction of collective international danger becomes an ordering process that conditions foreign policy strategizing.

Depuis la naissance de la Suisse moderne en 1848, sécurité a constamment rimé avec neutralité. De nos jours, cette dernière reste encore perçue par une large majorité de Suisses comme une garantie de protection face aux tumultes du monde. Cependant, dans la pratique, cette singularité est remise en question. Notre article dans Questions internationales démontre que dans un monde interdépendant, l’impératif de coopération, indispensable pour gérer les menaces avant tout globales et transnationales, s’accompagne d’une discrète mais profonde transformation du paysage sécuritaire du pays situé au cœur de l’Europe.

Depuis la naissance de la Suisse moderne en 1848, sécurité a constamment rimé avec neutralité. De nos jours, cette dernière reste encore perçue par une large majorité de Suisses comme une garantie de protection face aux tumultes du monde. Cependant, dans la pratique, cette singularité est remise en question. Notre article dans Questions internationales démontre que dans un monde interdépendant, l’impératif de coopération, indispensable pour gérer les menaces avant tout globales et transnationales, s’accompagne d’une discrète mais profonde transformation du paysage sécuritaire du pays situé au cœur de l’Europe.